Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) presents a complex clinical picture, with approximately 25% of patients experiencing their initial symptoms in the bulbar region—the area controlling speech, swallowing, and facial movements. These early manifestations often serve as crucial diagnostic indicators, yet they can be subtle and easily overlooked during routine medical examinations. Understanding the progression and characteristics of tongue and facial symptoms becomes essential for healthcare providers and patients alike, as bulbar-onset ALS typically follows a more aggressive course than limb-onset presentations.

The bulbar region encompasses critical motor functions that we rely on daily for communication and nutrition. When ALS affects these neural pathways, the resulting symptoms can profoundly impact quality of life and present unique challenges for both diagnosis and management. Recognition of these early warning signs can significantly influence treatment decisions and patient outcomes.

Bulbar dysfunction manifestations in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients

Bulbar dysfunction represents one of the most challenging aspects of ALS management, affecting the cranial nerves responsible for vital functions including speech production, swallowing coordination, and facial muscle control. The bulbar region of the brainstem contains motor nuclei that control these essential activities, and when ALS targets these areas, patients experience a cascade of progressive symptoms that significantly impact their daily functioning.

The presentation of bulbar symptoms varies considerably between individuals, with some patients experiencing rapid progression whilst others maintain functional abilities for extended periods. Early recognition of these manifestations proves crucial for implementing appropriate interventions and support systems. Healthcare providers must understand that bulbar symptoms eventually affect nearly all ALS patients, regardless of their initial presentation pattern.

Progressive dysarthria patterns and speech deterioration stages

Dysarthria in ALS follows predictable patterns of deterioration, beginning with subtle changes in articulation and progressing to complete speech loss. Initial symptoms often include difficulty with consonant pronunciation, particularly sounds requiring precise tongue positioning such as ‘l’, ‘r’, and ‘t’. Patients frequently report that others begin questioning their clarity during telephone conversations before they themselves recognise the changes.

The progression typically involves several distinct stages. Early-stage dysarthria presents with mild slurring and reduced speech rate, whilst maintaining intelligibility for familiar listeners. Intermediate stages show marked articulation difficulties, nasal resonance changes, and significant reductions in speech volume. Advanced dysarthria renders speech largely unintelligible, requiring augmentative communication devices for effective interaction.

Speech deterioration patterns also involve prosodic changes, including altered rhythm, stress patterns, and intonation. These modifications can affect the emotional expressiveness of communication, adding psychological burden to the physical challenges. Monitoring these changes helps clinicians assess disease progression and timing for assistive technology interventions.

Dysphagia severity assessment using ALSFRS-R bulbar subscale

The ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R) bulbar subscale provides standardised measurements for tracking swallowing function decline. This assessment tool evaluates speech clarity, salivation control, and swallowing efficiency using a four-point scale for each domain. Regular monitoring through this instrument helps predict nutritional risks and guides decisions regarding feeding tube placement.

Dysphagia progression in ALS typically begins with difficulty managing thin liquids, progressing to problems with mixed consistencies and eventually solid foods. Patients often develop compensatory strategies unconsciously, such as avoiding certain textures or taking smaller bites. However, these adaptations may mask the true severity of swallowing impairment until significant weight loss occurs.

Clinical assessment must include evaluation of oral preparatory phase dysfunction, delayed swallow initiation, and reduced laryngeal elevation. Silent aspiration represents a particularly concerning development, as patients may not exhibit obvious signs of choking whilst still experiencing pneumonia risks. Video fluoroscopic swallowing studies provide detailed information about swallowing mechanics and safety.

Pseudobulbar affect episodes and emotional lability recognition

Pseudobulbar affect (PBA) occurs in approximately 50% of ALS patients, presenting as episodes of involuntary laughing or crying that are disproportionate to the emotional trigger or situation. These episodes can be particularly distressing for patients and families, as they may be mistaken for depression or inappropriate emotional responses. Understanding PBA as a neurological symptom rather than a psychological condition is crucial for proper management.

Recognition of PBA involves identifying the characteristic features of these episodes: they typically last several minutes, occur with minimal provocation, and cannot be voluntarily controlled by the patient. The emotional expression may be completely incongruent with the patient’s actual emotional state, leading to social embarrassment and withdrawal from activities.

Sialorrhea management and drooling progression indicators

Excessive salivation, or sialorrhea, affects approximately 75% of ALS patients and results from impaired swallowing rather than increased saliva production. The inability to manage normal saliva volumes leads to drooling, choking episodes, and social embarrassment. Thick, tenacious secretions can be particularly problematic, creating additional swallowing challenges and potential airway complications.

Assessment of sialorrhea severity involves evaluating both objective measures (tissue usage, clothing changes) and subjective impacts (social avoidance, sleep disruption). The progression typically follows swallowing decline, with patients initially managing saliva through conscious effort before losing this compensatory ability.

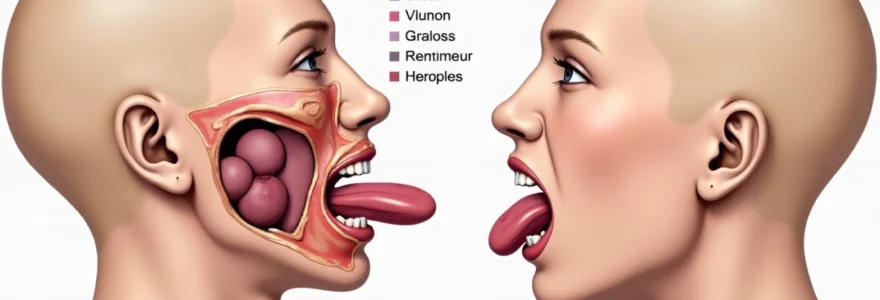

Fasciculations and muscle atrophy detection in orofacial regions

Fasciculations represent one of the most characteristic signs of motor neuron degeneration in ALS, and their presence in orofacial regions often provides early diagnostic clues. These involuntary muscle twitches result from spontaneous firing of motor units as they undergo denervation, creating visible rippling movements under the skin surface. In the context of bulbar ALS, fasciculations most commonly appear in the tongue, though they may also affect facial muscles, jaw muscles, and even the soft palate.

Detection of fasciculations requires careful clinical observation, as these movements can be subtle and intermittent. The tongue represents the most reliable site for fasciculation observation in bulbar ALS, with studies showing that tongue fasciculations occur in approximately 65% of patients with bulbar involvement. Healthcare providers must differentiate true fasciculations from normal tongue movements or anxiety-related tremors, which can sometimes be challenging during routine examinations.

Tongue fasciculation patterns and fibrillation potentials

Tongue fasciculations in ALS display characteristic patterns that can aid in diagnosis and disease monitoring. These involuntary contractions typically appear as rippling or worm-like movements across the tongue surface, most easily observed when the tongue is at rest within the mouth. The fasciculations may be focal, affecting only small areas of the tongue, or more widespread, involving multiple regions simultaneously.

Electromyographic studies reveal the underlying electrical activity associated with these visible fasciculations. Fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves on needle EMG provide objective evidence of denervation, supporting the clinical observation of fasciculations. The combination of clinical fasciculations and abnormal EMG findings strengthens the diagnostic evidence for motor neuron disease.

The relationship between fasciculation frequency and disease progression remains complex. Some patients experience prominent fasciculations early in their disease course, whilst others may have minimal visible fasciculations despite significant functional impairment. Monitoring fasciculation patterns over time can provide insights into disease activity and help guide treatment decisions.

Masseter muscle weakness and jaw closure difficulties

Masseter muscle involvement in ALS leads to progressively impaired jaw closure strength, affecting both chewing efficiency and facial appearance. Patients initially notice difficulty with tougher food textures, gradually progressing to problems with softer foods and eventually liquids. The weakness typically develops asymmetrically, creating uneven bite forces and potential temporomandibular joint complications.

Clinical testing of masseter strength involves assessing maximum bite force and endurance during sustained contractions. Quantitative measurements using bite force transducers can provide objective data for tracking progression, though clinical assessment through palpation during voluntary contractions often suffices for routine monitoring. Patients may develop compensatory chewing patterns that can mask early weakness.

Facial nerve involvement and lower motor neuron signs

Facial nerve involvement in ALS typically manifests as lower motor neuron signs affecting facial expression muscles. Unlike upper motor neuron facial weakness seen in stroke, ALS-related facial weakness affects both upper and lower facial regions equally. Patients may notice reduced facial expression range, difficulty with lip closure, and problems with facial gestures during communication.

The progression of facial weakness often follows a predictable pattern, beginning with subtle asymmetries during voluntary movements and advancing to more obvious weakness affecting both sides of the face. Lip seal dysfunction becomes particularly problematic as it contributes to drooling and affects articulation quality. Assessment involves testing individual facial muscle groups and observing spontaneous facial expressions during conversation.

Perioral muscle wasting and lip seal dysfunction

Perioral muscle atrophy affects the muscles surrounding the mouth, including the orbicularis oris, which is crucial for lip closure and articulation. This wasting becomes visually apparent as thinning of the lips and development of perioral wrinkles. Functional consequences include difficulty with labial consonant production, problems maintaining lip closure during swallowing, and challenges with oral containment of food and liquids.

Lip seal dysfunction represents a significant functional impairment that affects multiple daily activities. Patients experience difficulty with drinking from cups without straws, maintaining oral hygiene, and producing certain speech sounds. The combination of reduced lip strength and altered sensation can make activities requiring precise lip control increasingly challenging.

Upper motor neuron signs in cranial nerve territories

Upper motor neuron involvement in cranial nerve territories produces distinctive signs that complement the lower motor neuron features typically associated with ALS. These manifestations include pathological reflexes, spasticity, and hyperreflexia within the bulbar region. The presence of upper motor neuron signs in combination with lower motor neuron features provides crucial diagnostic evidence for ALS, distinguishing it from other motor neuron disorders that may present with similar symptoms.

Spastic dysarthria represents one of the most common upper motor neuron manifestations in bulbar ALS. This presents as strained, effortful speech with a harsh vocal quality, slow speech rate, and imprecise consonant articulation. Unlike the flaccid dysarthria associated with lower motor neuron involvement, spastic dysarthria maintains vocal strength but loses flexibility and coordination. Patients often describe feeling as though their tongue and lips are “stiff” or “heavy” during speech attempts.

Pathological reflexes in the bulbar region include an exaggerated jaw jerk reflex and the presence of snout, suck, and palmomental reflexes. These primitive reflexes, normally suppressed in healthy adults, become prominent when upper motor neuron control is compromised. Clinical examination should systematically assess for these reflexes, as their presence supports the diagnosis of upper motor neuron involvement in the context of other bulbar symptoms.

Emotional lability, while potentially related to pseudobulbar affect, also reflects upper motor neuron dysfunction affecting the corticobulbar pathways that control emotional expression. This manifests as reduced voluntary control over emotional responses, with patients experiencing difficulty suppressing laughter or tears once initiated. The combination of emotional lability with other upper motor neuron signs provides additional diagnostic support for ALS.

The coexistence of upper and lower motor neuron signs within the same functional territory represents a hallmark feature of ALS that distinguishes it from other neurodegenerative conditions affecting the bulbar region.

Differential diagnosis considerations for orofacial ALS symptoms

The differential diagnosis of orofacial symptoms suggestive of ALS requires careful consideration of several conditions that can present with similar clinical features. This diagnostic challenge becomes particularly complex because bulbar symptoms can appear in isolation initially, before more characteristic ALS features develop. Healthcare providers must systematically evaluate alternative diagnoses whilst monitoring for the development of additional signs that would support or refute an ALS diagnosis.

The importance of accurate differential diagnosis cannot be overstated, as several conditions that mimic bulbar ALS have different treatment approaches and prognoses. Some conditions may be treatable or have more favourable outcomes, making early and accurate diagnosis crucial for optimal patient management. Clinical expertise in recognising subtle distinguishing features often determines diagnostic accuracy and subsequent treatment decisions.

Kennedy disease versus ALS bulbar presentation distinctions

Kennedy disease, also known as spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, can present with bulbar symptoms that closely resemble those seen in ALS. However, several key distinguishing features help differentiate these conditions. Kennedy disease typically affects only males due to its X-linked inheritance pattern, whilst ALS shows a slight male predominance but affects both sexes. The progression of Kennedy disease is generally much slower than ALS, with symptoms developing over decades rather than months to years.

Additional distinguishing features include the presence of gynaecomastia and testicular atrophy in Kennedy disease, which are not associated with ALS. Fasciculations tend to be more prominent and persistent in Kennedy disease, particularly affecting the facial and perioral muscles. Genetic testing for CAG repeat expansions in the androgen receptor gene provides definitive diagnosis for Kennedy disease when clinical suspicion exists.

Progressive supranuclear palsy orofacial feature comparisons

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) can present with bulbar dysfunction that overlaps with ALS symptoms, particularly in the early stages. However, PSP typically includes characteristic eye movement abnormalities, including vertical gaze palsy and reduced blink rate, which are not features of ALS. The speech patterns in PSP tend to be more monotonous and hypophonic compared to the variable presentations seen in ALS.

Swallowing difficulties in PSP often involve the pharyngeal phase more prominently than the oral preparatory phase, whereas ALS affects both phases relatively equally. Cognitive changes and behavioural alterations occur more commonly and earlier in PSP compared to ALS, where cognitive involvement typically occurs later in the disease course and affects a smaller percentage of patients.

Myasthenia gravis bulbar symptoms differentiation protocol

Myasthenia gravis presents particular diagnostic challenges when differentiating from bulbar ALS, as both conditions can cause dysarthria, dysphagia, and facial weakness. However, myasthenia gravis characteristically shows fatigability, with symptoms worsening with sustained activity and improving with rest. This fluctuating pattern contrasts with the progressive, non-fluctuating weakness seen in ALS.

The response to anticholinesterase medications provides a valuable diagnostic test for myasthenia gravis. Patients with myasthenia typically show temporary improvement in bulbar symptoms following edrophonium administration, whilst ALS patients show no response. Additionally, myasthenia gravis commonly affects extraocular muscles, causing diplopia and ptosis, which are rarely seen in ALS. Serological testing for acetylcholine receptor antibodies supports the diagnosis of myasthenia gravis in appropriate clinical contexts.

Clinical assessment tools for ALS orofacial manifestations

Comprehensive clinical assessment of orofacial manifestations in ALS requires a systematic approach using validated tools and standardised examination techniques. The complexity of bulbar function necessitates multi-modal assessment strategies that capture both subjective patient experiences and objective clinical findings. These assessment tools serve multiple purposes: establishing baseline function, monitoring disease progression, guiding treatment decisions, and evaluating intervention effectiveness.

The ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R) remains the gold standard for tracking functional decline in ALS, with specific items addressing speech, salivation, and swallowing. However, this scale may lack sensitivity for detecting subtle changes in bulbar function, particularly in early disease stages. Supplementary assessment tools often provide more detailed information about specific aspects of bulbar dysfunction.

Speech assessment protocols should include both perceptual evaluation by trained clinicians and instrumental measures when available. Acoustic analysis can quantify changes in voice quality, speech rate, and articulatory precision over time. These measurements provide objective data that can detect changes before they become clinically apparent, allowing for earlier intervention planning.

Systematic clinical assessment using validated tools enables clinicians to track disease progression objectively and make informed decisions about timing for interventional strategies and supportive care measures.

Swallowing assessment requires particular attention to safety considerations, as aspiration risk increases with disease progression. Clinical bedside swallowing evaluations can identify obvious signs of dysfunction, but instrumental assessments such as

videofluoroscopic swallowing studies or fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing provide detailed visualization of swallowing mechanics and can detect silent aspiration. These instrumental assessments become crucial when clinical evaluation suggests swallowing impairment but the full extent of dysfunction remains unclear.

Standardized oral motor examination protocols should evaluate strength, range of motion, and coordination of oral structures. Assessment of tongue strength using standardized resistance techniques, lip closure measurements, and jaw excursion ranges provides quantifiable data for tracking progression. Digital pressure sensors and specialized measurement devices can enhance the objectivity of these assessments when available in clinical settings.

Quality of life measures specific to bulbar dysfunction help capture the patient’s subjective experience and guide supportive care decisions. Tools such as the ALS-Specific Quality of Life instrument include items addressing communication difficulties and eating challenges, providing insights into the psychosocial impact of bulbar symptoms that may not be apparent through purely functional assessments.

Neurophysiological testing and electromyographic findings

Electromyographic studies play a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis of ALS and characterizing the extent of motor neuron involvement in orofacial regions. Needle electromyography of bulbar muscles can detect denervation changes before clinical weakness becomes apparent, making these studies particularly valuable in early disease stages. The combination of clinical examination findings with electrophysiological evidence strengthens diagnostic certainty and helps exclude other conditions that may present with similar symptoms.

Standard EMG protocols for suspected bulbar ALS should include examination of multiple cranial nerve-innervated muscles, including the tongue, masseter, and facial muscles. The tongue represents the most accessible and informative muscle for EMG evaluation in bulbar ALS, as it frequently shows early denervation changes and can be examined relatively easily. Abnormal spontaneous activity, including fibrillations and fasciculations, provides objective evidence of lower motor neuron dysfunction.

Motor unit potential analysis reveals characteristic changes in ALS, including increased amplitude, prolonged duration, and polyphasia. These changes reflect the reinnervation process as surviving motor neurons attempt to compensate for those that have been lost. The recruitment pattern analysis shows reduced recruitment with firing rate acceleration, indicating that fewer motor units are available but those remaining must fire at higher rates to generate force.

Nerve conduction studies typically remain normal in ALS, which helps differentiate it from peripheral neuropathies that might present with similar symptoms. However, compound muscle action potential amplitudes may be reduced in muscles showing significant denervation, reflecting the loss of functional motor units. Sensory nerve conduction studies should be completely normal in pure ALS, as sensory involvement suggests alternative diagnoses.

The electrophysiological signature of ALS combines evidence of denervation in multiple muscle groups with preserved sensory function, creating a distinctive pattern that supports clinical diagnosis when interpreted in the appropriate clinical context.

Repetitive nerve stimulation studies help exclude myasthenia gravis and other neuromuscular junction disorders from the differential diagnosis. In ALS, these studies typically show normal responses without decremental patterns, unlike the characteristic decremental response seen in myasthenia gravis. This distinction becomes particularly important when evaluating patients with isolated bulbar symptoms where the differential diagnosis remains broad.

Advanced neurophysiological techniques, including cortical stimulation studies, can provide evidence of upper motor neuron involvement by demonstrating prolonged central motor conduction times or absent responses. These studies complement the clinical examination findings and help establish the presence of both upper and lower motor neuron involvement required for ALS diagnosis.

The interpretation of electromyographic findings must always consider the clinical context and progression pattern. Single abnormal studies may not be diagnostic, particularly in elderly patients where some denervation changes can occur as part of normal aging. Serial EMG studies demonstrating progressive denervation changes provide stronger evidence for active motor neuron disease than isolated abnormalities.

Quantitative EMG techniques, including motor unit number estimation and decomposition-based quantitative EMG, offer more sophisticated approaches to characterizing motor neuron loss. These techniques can detect subclinical changes and may prove useful for monitoring disease progression and evaluating treatment responses in clinical trials, though they require specialized equipment and expertise not available in all clinical settings.

The timing of electrophysiological studies requires careful consideration, as these investigations can be uncomfortable for patients with bulbar symptoms. Early studies help establish diagnosis and baseline function, while follow-up studies may be indicated if clinical progression differs from expected patterns or if new symptoms develop that might suggest alternative diagnoses. The benefits of EMG confirmation must be weighed against patient comfort and the invasive nature of needle examinations in this vulnerable population.

Good health cannot be bought, but rather is an asset that you must create and then maintain on a daily basis.

Good health cannot be bought, but rather is an asset that you must create and then maintain on a daily basis.